As Tehran’s influence collapses in Syria and Lebanon, Ankara is stepping into the void, posing a new and complex threat to Israel’s north.

(May 27, 2025 / JNS)

With Hezbollah severely weakened and Bashar Assad’s army dismantled, organizers of a conference on security in Israel’s north shifted their focus beyond its immediate neighbors to Turkey, Iran and Russia—each vying to fill the power vacuum in Lebanon and Syria.

Titled “Reshaping the Northern Front,” last week’s conference hosted by the Alma Research and Education Center—a think tank focused on Israel’s northern security challenges—was an early attempt at using open-source intelligence to delineate the geopolitical landscape following last year’s abrupt collapse of Iran’s Shi’ite axis north of Israel.

At the conference, held at Kibbutz Lohamei Hageta’ot, a community established by Holocaust survivors eight miles from the border with Lebanon, experts on the region and beyond noted that Israel’s military achievements against Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the fall of the Assad regime in Syria in 2024, had removed a major threat.

But this, they warned, set the stage for a Sunni takeover backed by Turkey—a hostile power stronger than Tehran, yet one more constrained by the potential loss of critical assets.

“Just like Iran in the past was the dominant power in Syria, the fear for many in Israel today is that Turkey may become the dominant external power there,” said Yaakov Lappin, JNS military correspondent and strategic affairs analyst at the Alma Center.

This could have profound consequences for Israel and particularly for its northern region, according to Hay Eytan Cohen Yanarocak, a Turkey expert at Tel Aviv University’s Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies.

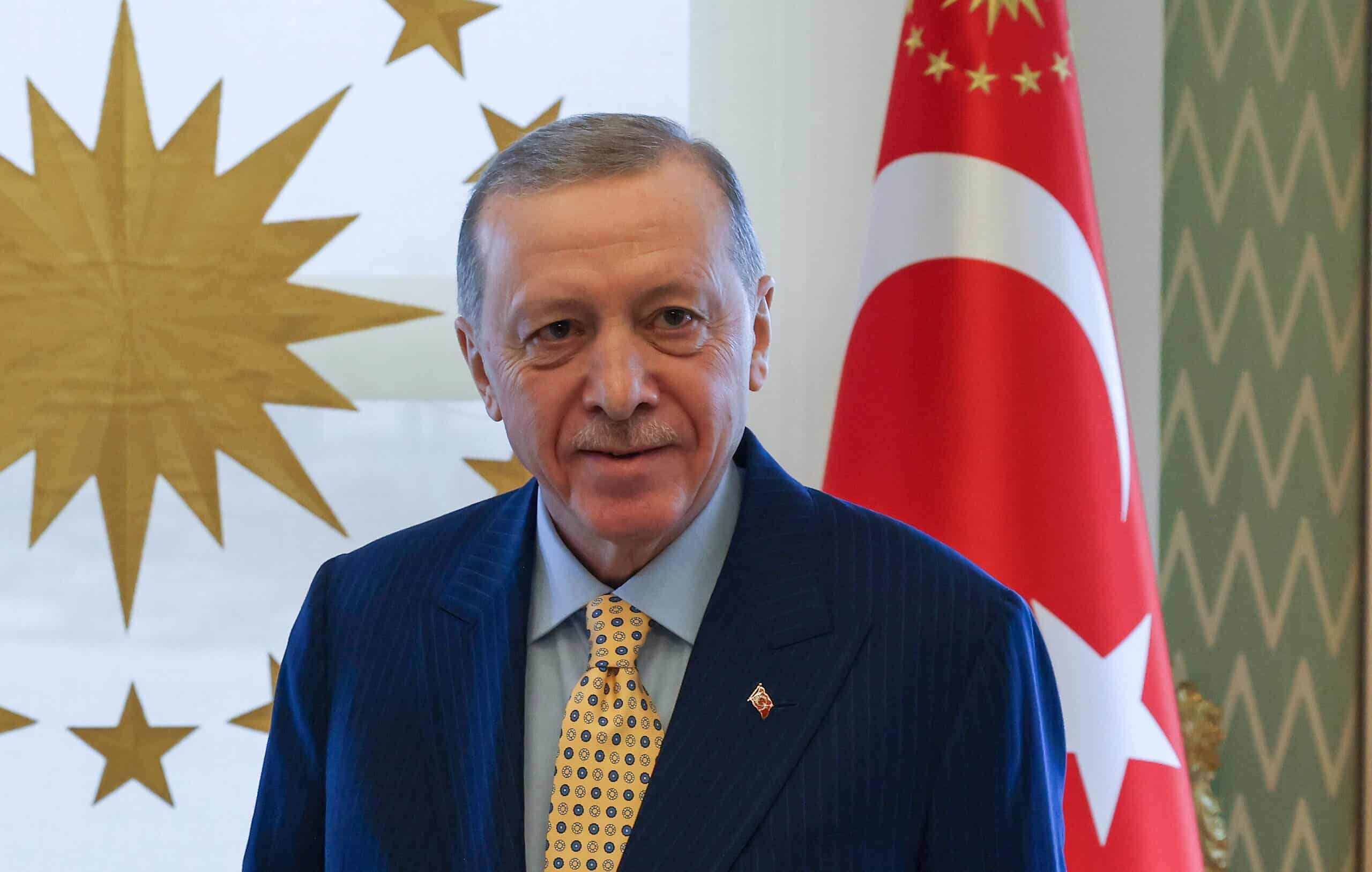

The threat of a Turkish takeover in Syria may be hard to grasp for Israelis who still think of Ankara as a key Israeli ally, as it had been for decades before President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan rose to power in 2003. Even under him, Turkey continued to draw millions of Israeli tourists and many investors.

War of words escalates into real threats

Erdoğan, leader of the Islamist AK Party, has instigated numerous diplomatic crises with Israel—most infamously by facilitating the 2010 flotilla attempting to breach Israel’s blockade of Hamas-run Gaza. He later participated in reconciliations with Jerusalem, often brokered by the United States. Still, trade and tourism continued well into the late 2010s.

In recent years, however, Erdoğan has plunged bilateral relations to new depths. The ongoing war in Gaza, which began on Oct. 9, 2023, has served as the backdrop for an unprecedented deterioration. Ambassadorial relations were severed, bilateral trade significantly reduced, and most direct flights between Israel and Turkey halted.

In parallel, Erdoğan has issued a series of belligerent statements against Israel, drawing harsh responses from Israeli officials.

In July, Erdoğan threatened to invade Israel, prompting a warning from then-Foreign Minister Eli Cohen not to “follow in the footsteps of Saddam Hussein.” Erdoğan, who has also inveighed against Jews, called Israel a “terror state,” accused it of committing genocide, and urged Muslim nations to unite against it.

Under Erdoğan—who faces mounting domestic opposition from liberal forces—Turkish officials labeled Israel the “main regional threat” to Turkey and the broader Middle East. Jerusalem and Ankara now exchange threats with an intensity once reserved for Israel’s relationship with Tehran.

The speed of this shift has created a disconnect between Israeli public perceptions of Turkey and its emerging role as a regional power that uses Syria to advance its anti-Israel policies, said Cohen Yanarocak.

Syria as a chessboard

“Ten years ago, I would’ve told you that Turkey stepping into Iran’s shoes was a ridiculous proposition. Today, unfortunately, I can only say that, yes, that’s very logical,” said Cohen Yanarocak.

He envisions a Turkish client state in Syria, possibly led, at least initially, by Ahmed al-Sharaa, the Sunni former Al-Qaeda commander who took control following Assad’s fall in December. Turkey had already moved to strengthen its military and political presence in northern and central Syria before Assad’s collapse, conducting attacks on Kurdish forces.

Israel, in turn, seized the eastern slopes of Mount Hermon from Syria and carried out dozens of airstrikes to prevent Assad’s heavy military arsenal from falling into the hands of rebel factions led by radical Islamists and jihadists.

The rebel advance came after Israel dealt devastating blows to Hezbollah—a longtime Assad ally whose battle-hardened forces had fought repeatedly to preserve the Shi’ite dictator’s rule during the civil war that began in 2011. Israel killed Hezbollah’s senior leadership, dismantled much of its ballistic infrastructure near the border, and forced it into a ceasefire agreement requiring its withdrawal from the frontier.

The Russian guardian

Moscow, which had been a major patron of Assad and maintains a military presence in Syria, views its foothold there as more than merely strategic, Dina Lisnyansky, a Tel Aviv University scholar of Middle East and Islamic Studies, said at the conference.

“Russia views itself as the guardian of the Christian Orthodox holy sites, and that’s part of its mission in Syria,” she said. Moscow will likely remain a part of the power dynamic in Syria, she added.

As Turkey and Israel advanced their competing strategic goals in post-Assad Syria, the two militaries, considered the most powerful in the Middle East, nearly clashed. Reports say their warplanes came into contact last month, prompting de-escalation talks mediated by Azerbaijan, according to Israel Hayom.

Turkey vs Iran: Similar goals, different tactics

Turkey, a NATO member, possesses one of the world’s largest and best-equipped armies, outfitted with advanced Western weaponry. Its capabilities and supply chains far surpass Iran’s.

However, Turkey is also far more constrained: A war with Israel would risk its ties with the U.S. and unravel decades of diplomatic bridge-building with the West, said Cohen Yanarocak. This places constraints on Israel, too, which “can’t operate against Turkey as it had against Iran,” he noted.

“Iran’s ring of fire around Israel relied on illegitimate proxies. Turkey is doing the same using legitimate states—Qatar and now Syria,” he said, noting U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent meeting with Syrian leader al-Sharaa.

The Washington connection

“This is the Turkish way: with suits, with ties, NATO membership, and a U.S. alliance. And I must say—it’s going great,” Cohen Yanarocak added, recalling Trump’s recent praise for Erdoğan, whom he called a “tough guy” that the American president “happen[s] to like.”

Some pro-Israel voices, including Trump advocates, have defended the president’s nonconfrontational stance toward Ankara.

Mike Doran, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, warned last month that a direct confrontation with Washington over Israel could empower Turkey’s anti-Israel factions. “If the United States plays its cards correctly, those elements will not be in the driver’s seat,” he said on the Israel Update podcast with Gadi Taub. “The United States has the capability to do that.”

Still, Trump’s Middle East policies—including efforts by his administration to restart nuclear talks with Iran—remain a source of concern for some.

Eric Mandel, founder and director of the Washington-based Middle East Political and Information Network (MEPIN), described Trump as an “isolationist.”

While his approach might grant Israel greater operational freedom, Mandel warned it came with strings attached. “The answer would be yes, under President Trump, Israel would have more slack—unless it conflicts with Trump’s vision. Then there’d be wrath,” he said.

Meanwhile, most of the 60,000 Israelis evacuated from the north in 2023 have returned, according to Sarit Zehavi, founder and president of the Alma Center, speaking at Kibbutz Lohamei HaGetaot.

Alma’s conference drew about 150 attendees, including foreign ambassadors, to a region that few dared visit last year amid Hezbollah’s missile and drone threats.

Despite the current calm, Zehavi urged vigilance.

“We know Hezbollah is preparing. They didn’t disappear. They are waiting for an opportunity,” she said, referencing the Oct. 7, 2023, surprise attack. “We must remember that last time, we handed it to them. We must make sure we don’t hand it to them again.”

Whatsapp

Whatsapp